An Emotional Approach to Painting

by Cathy Locke and Jennifer Almodova

A Discussion by Two Artists: Cathy Locke (CL) and Jennifer Almodova (JA)

JA – When did your perceptions of how you give value to art move to a new paradigm?

CL – After about ten years of painting I began feeling unsatisfied with my work. I felt my work was too technically focused and lacked any dimension.

JA – There is an inherent difficulty in shifting forces with your work. It requires you to forge an alliance in your own being, it is just a different language.

CL – Correct, I felt pretty blind, it was certainly uncharted territory. I started journaling, making lists of various emotions I wanted to capture in a painting. Then I would do small abstract studies of those emotions. I was asking myself, “How could I show this emotion visually? What marks do I make, what colors and tonal values? When you are trying to build your skills as a painter in the terms of technique, you search for that teacher that has better skills than you. When you shift to judging your work in terms of emotion, the parameters that measure your success totally change.

JA – The language of realism is universally recognizable. I want to suggest that language of the realm visually that you are talking about is very different and there aren’t systems of codification, to be able to critique the work from that point of view. It is exercising the feeling and emotional muscles, as opposed to just the visual muscles.

CL – It has only been very recently that I could even use a word like “negotiate." Before when I did strictly realistic work I would finish a painting and pretty much frame it right away. Its worth was only financial. Now, I find I finish work I set it aside and I move onto the next. I reserve judgment on it. It is a much more freer way to work.

Available for Purchase

JA – Sounds to me like even in grad school you were making a change from a skillful intellectual technique-based reality to a more inner guided reality, more emotional and visceral. Going from an outer criteria, to an inner criteria. You were coming into your own authority at the time, in an educational context that didn’t understand this. That you were on a path that was not part of their lexicon.

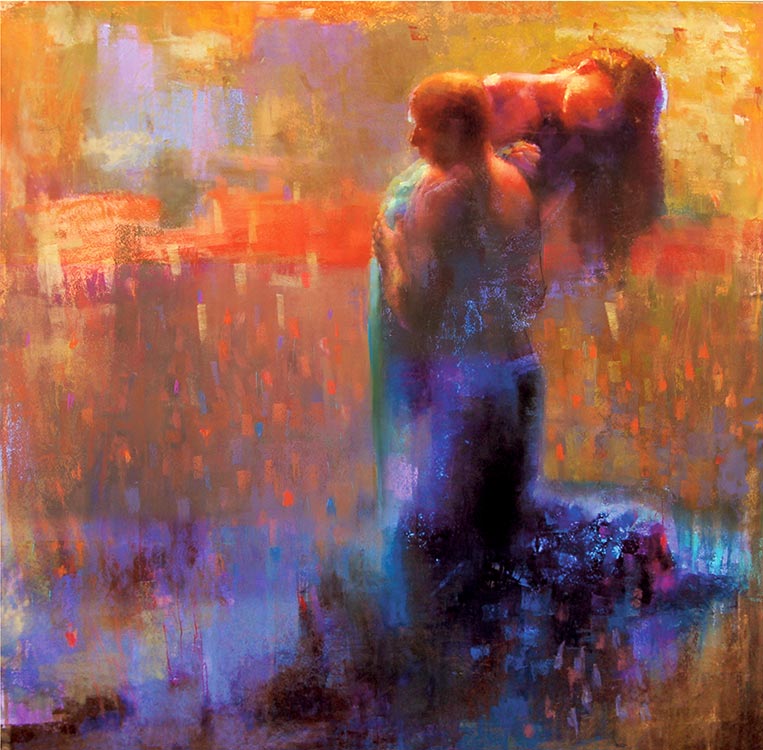

CL – About half-way through grad school I started this shift in my work. As I came off of a path of technical focus and onto a path of emotional focus, I was a total beginner with little clarity. I was lucky to find a number of instructors who understood this shift and were able to help me. I also started to notice that my approach to the very way I worked on a painting began to change. When I was technically focused I would carefully hover over a canvas for hours on end. Changing my focus to be emotionally based, my process becomes much more about what emotion I carry within me and physically how I go about expressing that emotion. My painting process has become more of a spiritual experience; it is much like being an orchestra conductor of energy and movement.

JA – Sounds like you now had a more intimate relationship with the work, where the work itself has its own life and you are nurturing it to bring it to whatever place it needs to be without time or financial restraints. What does this do for your work, your relationship to the work to not have those time and financial restraints?

CL – The creative process is such that not every piece of artwork you do will be saleable. Allowing yourself the space to explore and even make mistakes is critical.

JA – Being in an educational context, how did you negotiate this?

CL – It was an issue of technique vs. emotional quality in the work. Ideally the two should merge, but in the beginning I had to focus more on the emotional quality of the work so that I could build those skills. For the most part the educational environment was focused on the technical quality of the work. However, there was one director who awarded my painting Moving Inward second place in the Academy of Art University's annual Spring Show, which was a big honor for me. Unfortunately, that director left, and the new director didn't care for my work. As with any form of recognition it comes down to an individual’s personal aesthetics. My fan club was crushed when my “masterpiece” Reaching was rejected for the following year’s Spring Show. Overall, I recieved a number of awards for this body of work and almost everything has sold.

JA – Your commitment to your work became more of a holistic process, rather than the intellect guiding you. Sounds like it is more kinetic, you are engaging your senses in an entirely new way when you paint, engaging your entire being.

CL – It became imperative that I develop a deep personal connection to my work. This commitment involved not turning back even though I wasn’t receiving recognition. The environment in my studio needed to support my creative process. When I enter my studio I create a bubble for myself as if I am completely isolated from any concern or worry. Then I begin what I call a spiritual dance.

JA – This is really fascinating to hear you talk about this because I am sensing there is really a sacred aspect to creating your work. It seems like you are transported and are transforming at the same time.

CL –It is a ceremony I do, where I close the doors of the studio and in doing so I consciously shut out all outside tension. It is really like being a conductor of your own energy. As you begin to work you have to trust that all of the things you have learned will be there. This process requires that you to be authentic. When you truly allow yourself to be authentic with your work, uniqueness comes forward. But, you have to be okay with whatever comes forward, to allow yourself this exposure. It’s a matter of moving out of your mind and painting with your heart.

JA –Often a student will come into one of my classes and say I don’t want to learn how to draw or learn about color, I just want to do it. I always find that a bit daunting because it feels like it disregards so much that has gone into the making of so many artists. It isn’t to say that someone couldn’t come in and do this work. It just feels like the path of the person would be just not analogous to what we are talking about here.

CL – I agree. It is almost unspoken among artists who have a lot of work under their belt, where there is a very deep respect that they all have for their teachers and all the people that have come before them. This is what I saw in Russia, I was in awe at how much these artists had accomplished and sacrificed.

JA – How did your time studying in Russia in 2003 help you?

CL – In Russia I was able to stand in front of painted canvases of work that I had never seen before. I was experiencing the work from a completely new paradigm. Since I had no intellectual data stored in my brain for these paintings, I didn’t analyze them from the thinking part of my brain. Instead, for the first time, I read the paintings by feeling them. This planted a small seed inside of me.

JA – Was it the paintings themselves or a readiness within you? Or something about both that gave birth to this new seed of awareness?

CL – I think the readiness in me wasn’t like I woke up that morning and felt a clearness in me that I was now “ready.” As an artist we build on our direction and process through our own journey, it gives us a history upon which we develop our own unique foundation.

JA – It sounds like you were tracking the frustration, you were noticing it; you were having a diminishing return with your realistic work. Sounds like the ability to commune with these paintings in Russia were the affirmation you needed to take you and turn you.

CL – Certainly to see and feel the work of these artists inspired my journey. I was very impressed by Nicoli Feshin’s layering technique and the abstraction it created. Seeing a large body of Wassily Kandinsky’s work had a huge impact on me as an artist. I could see how Kandinsky started off realistically, then started breaking down form, until finally going completely abstract. He showed me how to be a conductor of energy. His abstract work became an explosion of emotion to me.

JA – I think we are really hitting on some key important things here. I know Kandinsky’s book on the spirituality of art is what I make my graduate students read.

CL – I had read that book too. I read that book more with my intellect, when I saw his work it was more of a visceral experience.

JA – It is the difference between sitting in an airplane on the runway and actually taking off. They are two different things.

CL – Exactly.

JA – Were there other Russian painters who helped open the door for you?

CL – Mikhail Vrubel greatly influenced me, both conceptually and technically. He embraced the good and bad emotional body within himself and painted a series of demons, for which he became famous. He also explored groundbreaking techniques, including cubism. A young Picasso called him a genius!

JA – If you were going to offer advice to someone who is feeling this type of frustration in their work; for those who realize they have something more to offer but can’t figure out how to do it; how would you suggest they proceed?

CL – Developing a deep personal connection to your work is very important. For some reason that seems to be missing with a lot of American artists, we seem to be focused only on selling our work. So, I ask you – Is it good art if it sells but you as the artist feels no connection with it?

Journal Entries

Exploration of abstract concepts that show the shift in the way I went about creating my art.

_________

Cathy Locke

Cathy Locke is an award-winning fine art painter, university graduate professor and published writer, specializing in Russian art of the 19th and 20th centuries. She is the editor of Musings-on-Art.org. Ms. Locke has received many accolades for her fine art, the list includes the Pastel Society of America, the West Coast Pastel Society, Pastel 100, the Northwest Pastel Society, New Mexico Pastel Society, Florida Pastel Society, Salon International, OPA and Connecticut Society of Portrait Artists. For her commercial work she has received accolades from Art Directors Club of New York, Society of Illustrators in Los Angeles, CA Magazine, Creativity 37 and Campaign Papers. Ms. Locke began her education with traditional art history, including studying in Europe at the Art Academy in Paris, with study at the Louvre, as well as the London Polytechnic Institute with work at the Tate Gallery. In the fall of 2003, she was able to study art in Russia. Ms. Locke holds a BFA from Art Center College of Design and a MFA from the Art Academy of Art, both with honors. She exhibits and sells her paintings throughout the United States.

Cathy Locke’s artwork – www.cathylocke.com

Jennifer Almodova

Jennifer Almodova earned a B.F.A. degree in Sculpture from Scripps College in Claremont, California, and a M.F.A. degree in Ceramic Sculpture with an emphasis in Watercolor Painting from San Francisco State University, where she studied with both Wesley Chamberlain and Stephen DeStaebler. She taught undergraduate and graduate courses at Louisiana Tech University in Ruston, Louisiana from 1985 to 1988, taught at the University of San Francisco from 1994 to 1996 and has taught at the San Francisco Academy of Art University for the last 15 years, since 1993.In the last four years, Jennifer has conducted private workshops throughout the western United States including California, Hawaii, Washington and Montana. She exhibits and sells her paintings in California, Hawaii and Montana, and her work hangs in collections across the United States, Europe and Asia.