Ivan Kramskoy: The Search for Artistic Truth

by Cathy Locke

“Unknown Woman,” 1883, oil on canvas, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

A master portrait artist and the founder of the Wanderers, Ivan Kramskoy (1837-1887), was committed to the equalities of all people. His father was a secretary in Russia’s first governmental body called the Duma, during a time when Russia first began a great shift in power from a single autocracy to a semi-legislative body. This had such a great influence on Kramskoy that he developed the belief in truth and justice for all mankind. After graduating from the equivalent of high school in 1850, Kramskoy worked as a clerk at the municipal duma. From 1857-1863, he studied historical painting at the Imperial Academy of Arts. In 1863, in his first political act for social reform, Kramskoy led a rebellion of fourteen students who were attending the Imperial Academy. These students, who became known as the Wanderers, demanded free choice in the theme for their paintings. As a result, Kramskoy left the Academy with a second-class art degree. Always the rebellious one, Kramskoy established the School of Drawing of the Society for the Encouragement of Artists in 1863. In one of life’s great ironies, he gave painting and drawing classes to the royal family for twenty years, starting in the late 1860’s, but it is important to note that his employer, Tsar Alexander II, was known as Alexander the Liberator because of his many reforms of Russia. This tsar emancipated the serfs and was the first ruler in Russia to allow local self-government. In 1869, Kramskoy actually rejoined the Imperial Academy, perhaps due to the tsar’s persuasion. That same year, Kramskoy visited Berlin, Dresden and Paris. In 1876, he traveled across Italy and, in 1878, France.

“Portrait of Sophia Ivanovna Kramskoy, the Artist’s Daughter,” 1882, oil on canvas, Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

Kramskoy is most well known for his portrait paintings. His style is characterized by a limited range of color, driven almost totally by tonal values and always rendered with great skill. His compositions are simply designed so that the focal point becomes the highly-rendered textures he creates for skin, hair and clothing. Above all, Kramskoy’s respect for his subjects always comes through. Kramskoy considered himself a poor colorist and admired his younger contemporaries for their use of color. In the 1870s he wrote this about the French Impressionists: “Just a small group of laughed at painters, but the future belongs to them.”

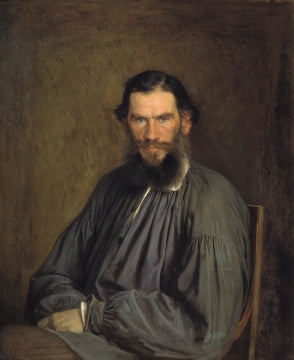

"Portrait of Leo Tolstoy," 1873. oil on canvas, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Due to Kramskoy’s strong political beliefs, he always painted people who were either democratic intellectuals or close friends. The great art collector, Pavel Tretyakov, commissioned Kramskoy to paint many of Russia’s cultural personalities. Upon learning the great portrait artist lived near Leo Tolstoy, who had refused Tretyakov’s request for a portrait several times, Tretyakov asked Kramskoy, “Please use all your charm to persuade him.” Apparently it took several attempts but Kramskoy and Tolstoy finally ended up becoming great friends. Tolstoy was working on his novel Anna Karenina at the same time Kramskoy was at his home painting his portrait. Tolstoy ended up creating a character in his book based on Kramskoy’s personality.

"Christ in the Wilderness," 1872. oil on canvas, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

In the early 1870s a new theme appeared in Kramskoy’s work regarding moral and ethical issues. The artist was searching for a way to portray the righteous ideals of his time. Turning to motifs taken from the Bible, Kramskoy painted Christ in the Wilderness (1872) to embody the ideal of man striving for self-sacrifice for the benefit of society. Kramskoy died in 1887 with a paint brush in his hand while painting the portrait of Doctor Rauhphus. For Kramskoy, artistic truth and beauty as well as moral and aesthetic values were inseparable. He was greatly beloved among his many friends and his work influenced his contemporaries in both technique and ideology. In 1885 he wrote to the great writer Alexi Suvorin, “In its essence Russian painting is just as different from European painting as that of Russian literature.”

Kramskoy’s Drawing Technique

In 1863, Kramskoy established the School of Drawing of the Society for the Encouragement of Artists in St. Petersburg. Most evenings the school had self-education programs organized by Kramskoy. Ilya Repin described the impassioned Kramskoy, rushing into the classrooms full of new ideas: “His eyes shone with excitement and soon his voice was quivering with passion over a new question that none of us had ever heard before.” On Thursday nights Kramskoy hosted a figure drawing group that would attract as many as forty to fifty people. Not only would artists come, but writers, poets, composers and intelligentsia attended as well. The artists would stack up art supplies on tables and invite guests to join in. As for models, Kramskoi would use other artists, guests or even his own family. His daughter, Sophia, often modeled.

During these evenings Kramskoy demonstrated the use of a drawing crayon called Sauce (saw-oose), a pastel-like crayon made of pigment, Chasov Yar clay and carbon. Sauce comes in a compressed stick which can be crushed using a mortar and pestle. The resulting powder can be used in drawing and is extremely potent when mixed with water. Sauce becomes inky if mixed with a lot of water, but can be amazingly subtle if water is mixed in sparingly. Powdered Sauce can be used as a dry medium like charcoal; it can be laid down dry then brushed over with clear water. Sauce comes in a variety of cool and warm grays, in a complete value range of white to black. These demonstrations would last for three hours and Kramskoy was the undisputed Sauce master, combining Sauce with white charcoal and colored pencils for a fabulous effect.

“Portrait of T.G. Shevchenko,” 1871, oil on canvas, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

“Mermaids,” 1871, oil on canvas, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

“Forest Warden,” 1874, oil on canvas, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

“Portrait of A. D. Litovchenko,” 1878, oil on canvas, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

“Portrait of Ivan Shishkin,” 1880, oil on canvas, Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

“Portrait of the Writer and Publicist Alexi Suvorin,” 1887, oil on canvas, Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

About the Author:

Cathy Locke is an award-winning fine art painter, professor, and published writer, specializing in Russian art of the 19th and 20th centuries. She is the editor of Musings-on-art.org.

Cathy Locke’s artwork – www.cathylocke.com