Rockwell Kent: A Champion of Peace

by Cathy Locke

![]()

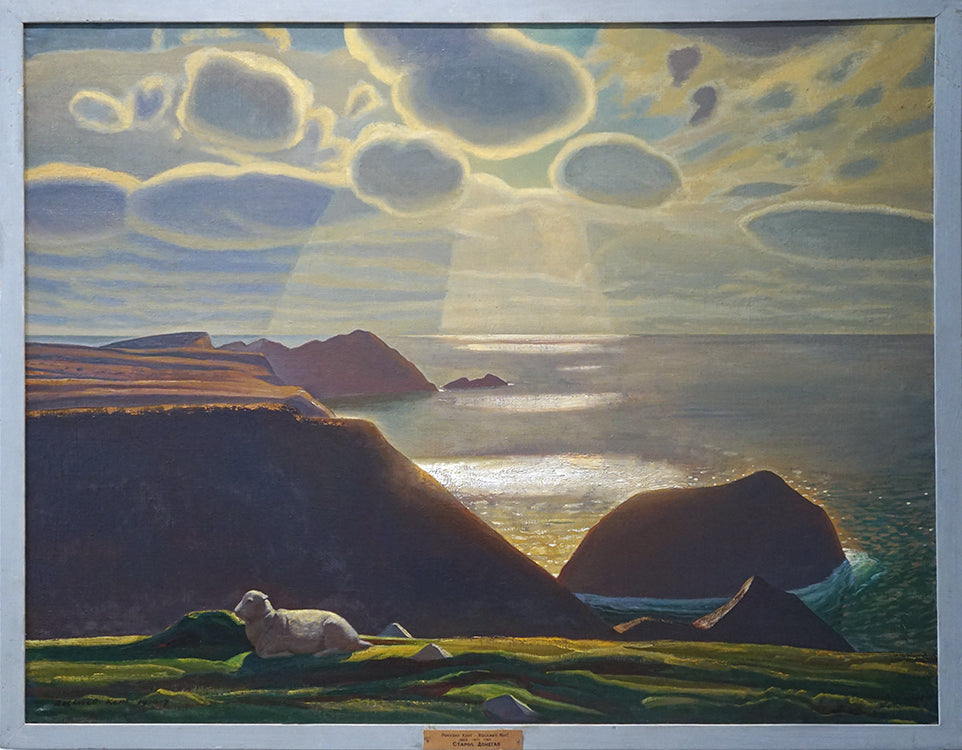

In 2014 the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia, annexed all of the buildings that encompass Palace Square. This impressive area forms a semicircle made up of a number of buildings, the two largest being the Winter Palace and the State Office Building. For many years the Hermitage Museum was only able to display about three percent of its collection, but with the additional 800 rooms provided by the State Office Building visitors can delight at the discovery of new artists now on display. It is for this reason that in 2018, I came upon work that utterly surprised me, an American artist in Russia! There they were, these absolutely serene landscape paintings by Rockwell Kent (1882-1971). The soft light that fell over rich colors spoke to me in the most peaceful way and I just had to stop and take in their beauty.

“Sturrall. Donegal. Ireland” (1927), oil on canvas, 87 x 112 cm, Hermitage State Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

![]()

Kent was a prolific painter, illustrator, photographer, filmmaker, designer, architect, intrepid traveler, writer, lecturer and political activist. He was the first of three children, born to George Rockwell Kent (1853-1887) and Sara Ann Holgate Kent (1854-1947). Kent’s father was a successful lawyer providing the family a lifestyle of comfort and privilege. When George Rockwell died of typhoid fever at the age of 34, the Kent household was reduced to a kind of gentile poverty. Rockwell was able to attend private schools due to the generosity of Sara’s wealthy sister Ellen Josephine Holgate Banker (known as “Auntie Jo”). An accomplished ceramicist, Auntie Jo came to live with the family at one point, providing artistic encouragement for the young Rockwell. In 1895, Auntie Jo took Kent to Europe for an art tour that included London, Dresden and The Hague.

Kent studied under a number of influential painters and theorists of his day. In the fall of 1900, he learned composition and design from Arthur Wesley Dow (1857-1922) at the Art Students League. He studied painting withWilliam Merritt Chase (1849-1916) for three summers between 1900 and 1902 at the Shinnecock Hills Summer School of Art. After this, Chase awarded Kent a full scholarship to the New York School of Art, which Chase had founded. It was here that he met fellow classmates George Bellows (1882-1925) and Edward Hopper (1882-1967). In the fall of 1905, Kent entered the class of Robert Henri (1865-1929) to study. “Much later Kent characterized the triad of influences that shaped his art at this time, ‘as Chase had taught us just to use our eyes, and Henri to enlist our hearts, now Miller called on us to use our heads.’”1

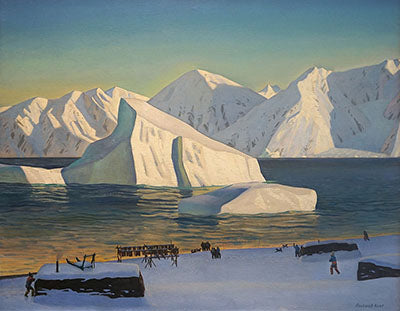

“Early November, North Greenland” (1933), 86 x 112 cm, Hermitage State Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

![]()

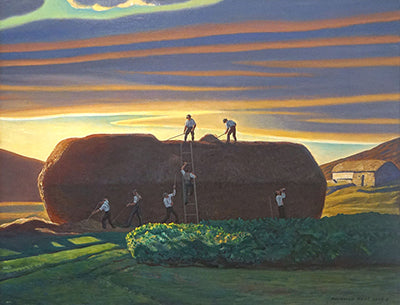

During the summer of 1903 in Dublin, New Hampshire, Auntie Jo secured an apprenticeship for Kent with painter and naturalist Abbott Handerson Thayer (1849-1921).2 Working with Thayer had a lasting impression on Kent helping him find his own unique voice as an artist. In 1905, Henri invited Kent to Monhegan Island, which is ten miles off the coast of Maine. Kent found its rugged and primordial beauty a source of inspiration and stayed there for the next six years painting and running an art school. In 1907, Auntie Jo arranged for Kent’s first one-man show at Clausen Galleries in New York of his first series of paintings of Monhegan, which was met with wide critical acclaim. These works formed the foundation of his lasting reputation as an early American modernist, and can be seen in museums across the country, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Seattle Art Museum, New Britain Museum of American Art, and the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Kent found inspiration in the austerity and stark beauty of the wilderness. He was called the modern Ulysses by one of his biographers, Constance Martin, and his art was inspired by extended sojourns to remote, sparsely inhabited places where his imagination could draw on the mystical. From 1914 until 1915 he and his first wife, Kathleen Whiting (1891-?), lived with their children on the island of Newfoundland. In 1922, he sailed to the Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego. The final stage of his odyssey took him to Greenland, first in 1929, again in 1931, and from 1934 to 1935. His paintings of land and seascapes from these often-forbidding locales convey the symbolist spirit, evoking the mysteries and cosmic wonders of the natural world. "I don't want petty self-expression," Kent wrote, "I want the elemental, infinite thing; I want to paint the rhythm of eternity."3 By his mid-forties Kent moved to an Adirondack farmstead that he called Asgaard, where he lived and painted surrounded by nature until his death.

Kent supplemented painting with commercial and book illustrations, which were primarily line drawings created in pen and ink or prints created from lithography or wood engravings. “The largest of his numerous projects were a three-volume illustrated edition of Moby Dick, The Complete Works of Shakespeare and The Canterbury Tales. Kent also wrote and illustrated books chronicling his adventures to Tierra del Fuego and – in three separate expeditions, the first of which included being shipwrecked – in Greenland. He completed a six-month lecture tour, served briefly as editor of Creative Arts, and published numerous articles on everything from the technique of making woodcuts to a vision of modern art …”4

While Kent was living with the Greenland Eskimos the economic collapse in Europe was fueling fascism. The United States was experiencing Prohibition, race riots and hooded moralists. “When Kent described to the Eskimos the coexistence, in his native land, of rampant unemployment and unparalleled wealth they laughed in disbelief.”5 Upon his return from Greenland in 1935, Kent became more committed to taking an active part in public affairs. After his book This is My Own was published in 1940, Kent was citated for his “subversive” activities as a member of the American League for Peace and Democracy, and the Descendants of the American Revolution.

Kent was like many others who were interested in the Soviet experiment. One of Kent’s most noteworthy involvements was serving as president of the International Workers Order (IWO). The society provided medical and funeral insurance to its 160,000 American members. In 1949, Kent went to Paris as part of an unofficial American delegation to the World Congress on Peace, which called for the banning of all nuclear weapons. He attended the second Peace Congress the following year and accepted an invitation to go to Moscow. His unauthorized foray into the USSR caught the attention of the U.S. State Department, which refused to renew his passport. “Though he regarded capitalism as “an outrageous, silly, cruel farce,” he believed in constitutional government and democracy. He wanted governments, like art, to speak for the greatest possible number of people.”6

On June 2, 1953, Kent meet with Wendell Hadlock, the director of the Farnsworth Art Museum in Rockland, Maine. During this meeting Kent was able to secure an exhibition for the following summer of his large collection of paintings, prints and drawings. Later that summer Kent was summoned to Washington, DC to appear before the Committee on Government Operations that was chaired by Senator Joseph McCarthy. He set off for the Capitol eager for the forum and armed with a statement as to the true nature and source of subversion in America. When asked if he was a member of the Communist Party Kent invoked the Fifth Amendment. Time magazine devoted several column inches, including a photograph of Kent’s Senate appearance. In August, the Farnsworth Museum’s trustees met and decided Kent’s exhibition would be indefinitely postponed. This came as a huge blow to Kent, who now had lost both his exhibition and a permanent place to house his life’s work.

By the age of 75 Kent had many friends and supporters in the Soviet Union. In fact, a celebration of his seventy-fifth birthday was held in Moscow in 1957, but Kent was unable to attend because he still did not have a passport. “An exhibition of his paintings – the first ever in that country by an American artist – had traveled to five Soviet cities during 1957 through 1958, drawing enthusiastic crowds wherever it went.”7 The U.S. Supreme Court finally ruled against the State Department and Kent received his passport. In 1960, declaring that “art belongs to those who love it most,” Kent gave his life’s work, a collection of several hundred paintings, drawings and prints to the Soviet Union. He subsequently became an honorary member of the Soviet Academy of Fine Arts and in 1967 the recipient of the International Lenin Peace Prize. Kent specified that his prize money be given to the women and children of Vietnam, both North and South.

Sources

- Constance Martin, Rockwell Kent and Richard V. West, Distant Shores: The Odyssey of Rockwell Kent, University of California Press; First Edition Softcover edition (August 7, 2000), page 13

- Henry John Steiner, Native Son – Rockwell Kent, Headless Horseman Blog, http://headlesshorsemanblog.com/native-son-rockwell-kent/

- Cited in C. Lewis Hind, Rockwell Kent in Alaska and Elsewhere, International Studio, vol. 67, no. 268 (June 1919), p. 112.

- Ellen Pearce, Rockwell Kent’s Forgotten Landscapes, Down East Books, Camden, Main, 1998, page 10

- Ellen Pearce, Rockwell Kent’s Forgotten Landscapes, Down East Books, Camden, Main, 1998, page 11

- Ellen Pearce, Rockwell Kent’s Forgotten Landscapes, Down East Books, Camden, Main, 1998, page 12

- Ellen Pearce, Rockwell Kent’s Forgotten Landscapes, Down East Books, Camden, Main, 1998, page 15

About the Author

Cathy Locke is an award-winning fine art painter, university graduate professor and published writer, specializing in Russian art of the 19th and 20th centuries. She is the editor of Musings-on-Art.org.

Cathy Locke’s artwork – www.cathylocke.com