Master Russian Impressionist

by Cathy Locke

2012 Retrospective on Konstantin Korovin (1861–1939)

During our visit to Moscow this summer, we were very fortunate to see a fabulous special exhibition of the work of Konstantin Korovin. The collection contained artwork spanning the artist's entire career, from early to mature pieces. This exhibition was of such high caliber that I am sure I will never see this much art by Korovin in one place again in my lifetime.

The last exhibition of Korovin’s work was at the Tretyakov Gallery in 1920, right before he immigrated to France. That exhibit was not as large as this year’s exhibition and Korovin had been deeply disappointed because only his early, “immature” work was exhibited. The United States has not had the benefit of a good introduction to Korovin's work. Considered as one of the greatest Russian Impressionists, Konstantin Korovin was a man of many talents for not only was he a painter, but he was also a theater designer and writer. As a painter, he was skilled in all genres: landscape, still life and portraits.

Konstantin Korovin was born in Moscow, the son of well-to-do parents of the merchant class. His father was a lawyer and his mother was very involved in music and painting. She raised two artists, in fact, as both of her sons, Sergey and Konstantin, were painters.

Korovin entered Moscow’s School of Painting and Architecture in 1875 at the age of fourteen. He studied architecture at first, but after a year he changed his major to painting. He later transferred to the Academy in St. Petersburg, but became disappointed in the methods they used and left school.

During his years at school, he had three professors who had a profound influence on him. The first was Vasily Perov, who was famous for his highly technical achievements in portraiture. The second was Alexi Savrasov, who experienced a tortured career with the highest highs and the lowest lows. One painting loved by many Russians, and probably one of Savrasov's most famous, is “The Rooks Have Come Back.” If you study Savrasov’s mature work you will see major influences on Korovin’s early work, especially in the color palette and composition.

Last but not least was Korovin’s third professor, Vasily Polenov. Polenov graduated from the Academy in St. Petersburg with what is known as a “top-level degree,” meaning he had won all the awards there was to win. When Korovin first started taking his classes, Polenov had just returned from Paris, bringing new techniques of the Impressionist painters back to Russia. Apparently, he was a beloved teacher and became very good friends with Korovin. Polenov had a country house in the suburbs of Moscow where Korovin was often a guest and where Polenov and Korovin painted together outdoors. Soon, Korovin became Polenov’s teacher because he had such a good eye for color.

Korovin has been considered the first Russian Impressionist because of an early painting “Portrait of a Chorus Girl,” which he probably did while studying with Polenov. The original date was recently discovered to be 1887. Korovin had painted over this date and put in 1883 because his friend, Valentin Serov, painted “Girl with Peaches” in 1887 and Korovin, who was always in competition with Serov wanted to say that he was the first Russian Impressionist, not Serov. Russia’s most famous artist, Ilya Repin, did not like this painting by Korovin and said this was just “painting for painting's sake”, with no real skill or thought.

Trip to the North

In 1894, Serov and Korovin made a trip north, visiting Finland, Sweden and northern Russia. Saava Mamontov financed the trip to promote a railroad he was building. Korovin discovered there was more variety of color in the north than anywhere else he had ever been.

At the Moscow exhibition, there was a wonderful portrait of Korovin painted by Valentin Serov. In the painting, Serov tries to imitate Korovin’s loose brushwork, depicting Korovin in a relaxed pose. On the wall behind Korovin are studies from their trip from which they had just returned. Although they were friends, their personalities were completely different. Korovin was very loose and fun-loving, while Serov wore a suit while he painted and was always very business-like.

The paintings from this trip were used to decorate Mamontov’s railway stations. These paintings disappeared after the 1917 revolution, but a few years ago they reappeared in the railway station. We were lucky to be able to see them at this retrospective exhibition, because they had not been exhibited in over eighty years.

Trip to Spain and Italy

In 1885, Korovin traveled to Paris and Spain, Saava Mamontov once again paid for the trip. Artist Mikhail Vrubel went with them. Both artists had a great time and were very influenced by the artwork they saw. Korovin wrote, "Paris was a shock for me … Impressionists… in them I found everything I was scolded for back home in Moscow."

Korovin was also inspired by Velázquez and Goya. Korovin’s painting, “At the Balcony. Spanish Women Leonora and Ampara,” painted in 1889, shows us the influences from these Spanish painters. Korovin exhibited this painting for the first time in 1900 at the Paris World Fair, where it won first prize.

The 1896 All Russia Exhibition

Mamontov employed Korovin’s skills again for the pavilion for the Far North Section at the Nizhny Novgorod Trade and Industry Fair. Using the paintings and sketches from his northern trip, Korovin created ten large canvases depicting various aspects of northern Russia and the Arctic lifestyle. After the closure of the exhibition, the canvases were eventually placed in the Yaroslavsky Rail Terminal in Moscow. In the 1960's, they were restored and transferred to the Tretyakov Gallery.

Not only had I never seen these paintings, I didn’t even know they existed. One thing you will notice when you look at these canvases is the influence of the Art Nouveau movement. All the elements in these paintings are highly designed, using lots of curving lines and shapes that are so characteristic of Art Nouveau. It was great to experience all these canvases together in one room; you could really see the effect Korovin was trying to create.

These same canvases were also exhibited at the Russian Artisan Department Pavilion at the World Exhibition in Paris in 1900. At this exhibition, Korovin received medals and the Légion d’honneur award for his work. He was given a teaching position at the Academy in St. Petersburg because of this work and, in 1905, he was elected as a full member of the Academy. This is quite an accomplishment for someone who never received a painting degree.

I want to note that for the fair in 1896, Mamontov had employed Mikhael Vrubel to paint a huge canvas titled, “The Princess and the Dream.” While he was working on it, Vrubel had another one of his bouts with depression and the painting was actually finished by Korovin and Vasily Polenov. The painting was rejected by the fair’s committee and never shown. Today, however, the painting sits in a room specially created for it at the main Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow.

Stage Designer

To understand Konstantin Korovin, you must know that the theater played a large role in his life. In fact, it became the principal way in which he made his living. In 1885, Saava Mamontov hired Korovin to design the set for his private opera. By 1900, Korovin had become the designer for the Imperial Theater in Moscow, which is known as the Bolshoi Theater. In 1910, he became the chief designer and the consulting artist for not only the Bolshoi in Moscow, but also the Mariinsky Theater in St. Petersburg.

Korovin was an innovator in the field of stage design. He changed the artist’s role, turning himself into a real artistic director instead of remaining a mere designer. Korovin designed the sets, the costumes, the shoes and the advertising. In his costume designs, Korovin specified the colors and textures to be used and always made sure they were comfortable to wear. His most famous sets included “The Snow Maiden” and “The Woman from Pskov” by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, and of course the famous play by Nikolai Rubinstein “The Demon,” which had such a profound affect on artist Mikhael Vrubel.

One of Korovin's sets was displayed at the exhibition this summer, which included a huge backdrop, costumes and shoes. These theater sets usually do not survive and this one had quite the story behind it. One of the opera singers bought the entire set, including the costumes and shoes, after the play had ended. In later years, the set was passed down to his children. Some time after World War II, the family, who was living outside of Paris, decided to sell their theater set and actually dragged all of it out for a yard sale. One of Polenov’s grandchildren just happened upon this yard sale and, recognizing what was there, bought the entire thing! The Polenov family then dragged the set back to Moscow, where they donated it to the Pushkin Museum. Voilà! Because of this miraculous event, we were able to see this set at the exhibition in July.

Two interesting side notes about Korovin:

- In 2010, Christie's auctioned off a sketch of a costume Korovin did for the “Snow Maiden,” which sold for £5479.

- During World War I, Korovin worked as a camouflage consultant at the headquarters of the Russian army.

Paris

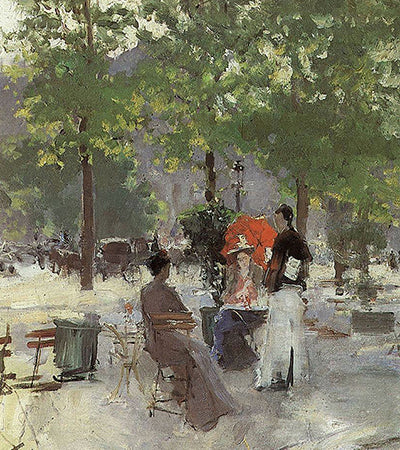

There are two important things to know about Konstantin Korovin: First, his life was the theater and second, he loved Paris. He would go to Paris almost every year to paint. He made a series of paintings of the boulevards at all different times of the day. He preferred painting in the evening because it reminded him of the theater and he thought the colors were more intense at night. Many of Korovin’s paintings look like the same scenes painted by Pissarro and Monet, but the technique is quite different. Pissarro and Monet worked with broken color, which was achieved by using small brushstrokes that overlapped, allowing the color underneath to show through. While the Impressionists used round brushes to create thinner strokes in a sweeping motion, Korovin used a larger brush called a flat, which allowed him to mold form with the direction of his brushstroke.

In 1923, Korovin moved to Paris on the advice of the Commissar of Education, Anatoly Lunacharsky, to cure his heart condition and help his handicapped son, Alexey, who had an accident during his childhood that caused both of his feet to be amputated. To finance his move to Paris, Korovin organized a large exhibition of his paintings. But all of these paintings were stolen and Korovin was left penniless. For years, he produced numerous paintings of Russian winters and Paris boulevards just to make ends meet. He lived in Paris as an émigré, remaining loyal to Impressionism until he died. Alexey, who became a noteworthy French-Russian painter, committed suicide in 1950.

Crimea

Korovin loved painting outdoors in Crimea, which is a peninsula in the Black Sea. Korovin had a summer residence near Gurzuf, and from there he was able to travel all over the Crimean area to paint, including the famous port of Sevastopol. In these paintings, you see a real shift in color reflecting the influence of Greece and the Mediterranean area. From 1900 to 1920, bright blues and pinks dominate these Crimean works, with a purity of color that appears to be straight out of the tube. Korovin loved music and often sang to himself while painting. In these paintings, you can feel his freedom and joy. Korovin was also a gifted writer and he wrote often about his country house in Gurzuf. Today, the artist’s former summer residence in Gurzuf has become the Korovin Art Center.

Still Lifes and Nocturnal Impressionism

Korovin painted a series of still lifes in Paris as well as in Gurzuf. His still lifes can be divided into two subjects – flowers and fish. He was a passionate fisherman and he wrote the sizes of the fish he painted on the back of each canvas. Korovin noticed the effect light had on color during the evening performances at the theater. He started to play around with this effect in his still life paintings and, in doing so, he created “Nocturnal” Impressionism. His inherent talent as a colorist helped him to employ the entire color spectrum, from tonal values to the most exotic contrast combinations. Two of his most famous nocturnal paintings are “Roses and Violets” (1912) and “Fish, Wine and Fruit” (1916). Fish, wine and fruit are probably the three things Korovin loved the most, and his depiction of them is one of my favorite paintings in the entire world. The paint is thickly applied in an impasto manner, brushstrokes follow form, and the color palette is rich.

Portraits

Perhaps I have saved the best for last, for among his many talents, Korovin was also a gifted portrait artist. His portrait of actress Tatiana Spiridonovna Lyubatovich, painted in 1880, was another competition with Serov’s work. Unlike Serov, Korovin makes no social comment on his subject but instead he depicts the actress in a carefree, relaxed manner. He uses beautiful back lighting with thick brushwork going in the direction of form, and he uses a soft pink brown palette.

He painted a similar portrait of Sofia Golitsyna in 1886. Her father was Prince Vladimir Golitsyn and she was married to Count Pavel Stroganov. She was famous for her evening salons where she invited leading poets and writers of the day to her home. A master of color harmony, Korovin balances the complementary colors of red and green. He uses a rose color throughout the painting; we see it muted in the background, in rich hues on Sofia’s face and hands, and then again throughout her dress. The rose color is complemented with the yellow green trim on her dress and in the background.

“Portrait of Ivan Morozov” (1903) is another one of my favorite paintings in all the world. Here Korovin captures one of the greatest art collectors of all time, as Morozov was one of the first to collect French Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art. He made his collection available to the public, so I am sure Korovin held a special place in his heart for this man. One of the first things I noticed about this painting was the beautiful impasto work on Morozov’s shirt and his face. Here, the brushwork becomes more important than the color. On Morozov’s face, Korovin sculpts the paint to build form. I feel this is the best portrait of Morozov that was done by any artist.

In the 1890's, Korovin married a woman he met through Mamontov’s theater. Even though the marriage was an unhappy one, they remained married throughout his life. However, Korovin was romantically involved with a number of women whom he also met through the theater. It was with one of these actresses that he had his son, Alexey, whom he adored. Alexey was also a painter and Korovin exaggerated the talents of his son, sometimes signing his own paintings with Alexey’s name.

Korovin painted a number of beautiful portraits of actresses, including Nadezhda Komarovskaya, Vera Aleekseevna Dorofeeva and Z. Pertseva. At the Moscow exhibit, the portraits of Z. Pertseva and the famous opera singer Feodor Chaliapin were hung next to one another and were most impressive. The brushwork in these portraits creates moving and energetic mark-making. The color used in the background is repeated again in the clothes and skin tones, creating a strong color harmony throughout both paintings. And, as is characteristic in all of Korovin’s portraits, both sitters are placed in relaxed, inviting poses.

Summary

The history of Russian impressionism is associated with Korovin’s paintings, which were characterized by their impulsive spontaneity. In most of his paintings, Korovin intentionally did not fully render the subjects, treating them as if they were studies. On his 50th birthday Konstantin Korovin defined his creativity as follows: "My major and the only ever-pursued purpose in art was beauty, esthetic influence on the viewer, the fascination of colors and shapes. No lecturing, no moral tendency to anybody ever.”

_______________________________

About the Author:Cathy Locke is an award-winning fine art painter, professor, lecturer and published writer, who specializes in Russian art of the 19th and 20th centuries. She is the editor of Musings-on-art.org.

Cathy Locke’s artwork – www.cathylocke.com