Russian Impressionism | 1875–1895

by Cathy Locke

In the late 1800s there were a number of substantial Russian collectors who supported the impressionist and post-impressionist movements. Ivan Morozov and Sergei Shchukin were two of these collectors who allowed Russian artists into their Moscow homes to study their huge collections. These artists became influenced by these paintings and began experimenting with the European style. Wassily Kandinsky decided to become an artist in 1895 after seeing Claude Monet’s Haystacks at an Impressionists’ exhibition in Moscow.

Unlike in Europe where the movement was clear-cut, Impressionism had a much more complex evolution in Russia. There was an explosion of artistic theory in Russia between 1860 and 1930, during which time Russian artists mixed various styles together. Because of this, Russian Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings can simultaneously be categorized under other movements such as Russian Symbolism, Cézannism, Neo-Primitivism and classic portraiture. These artists also worked under numerous art groups including the World of Art, the Blue Rose, Jack of Diamonds and the Union of Artists.

When European Impressionism first appeared in Russia it went virtually unnoticed. Unlike their European counterparts, Russian Impressionists did not challenge existing traditions - instead their paintings displayed extremely accomplished academic training. In the late 1870s the portraitist Ivan Kramskoi summed up the popular view of the European Impressionist movement when he said that it was nothing more than the “aspiration to fill the picture with light and color.” The Russian Impressionists clearly did not work in the same manner as the French Impressionists of the same period. The French worked in brighter colors, whereas the Russians used a more complex system of mixing color. Even the very definition of the word “impression” holds a different meaning from French to Russian. In French, it means “to retain the energy to impress,” whereas the same word in Russian translates as “vpechatlenie,” which comes from the word “pechal” meaning “sorrow.” This is why you will notice that Russian Impressionism is more directed at the heart than to the eye.

The Russian Impressionism of the 1880s reflects lyrical interpretations of life. Never before had there been so many paintings of childhood or poetic scenes of the everyday lives of the Russian people. This period is considered the most romantic period in the history of Russian Impressionism. Artists started creating dynamic and fragmentary compositions painted in an energetic, study-like manner. There was a rejection of narrative and an aspiration towards “gratifying” visual appeal. Unlike the French Impressionists, the Russian artists of the 1880s mixed their paints on the palette. As in Scandinavia and Germany, the Russian Impressionists were indifferent to the spectrally pure paints and blue-violet shadows of the French.

In Russia during the 1880s, paintings with social commentary by the Wanderers and paintings in the style of Critical Realism were by far the most popular with the public. European Impressionism rejected academic motifs and instead focused on the beauty of everyday reality void of a narrative or social criticism. These artists often worked in plein-air settings, giving their paintings a fresh, almost unfinished snapshot of life. By 1886 Russian artists were just starting to move away from heavy subject matter to embrace lighter themes of everyday life. However, this shift from paintings with a strong narrative to those of a lighter note was not met favorably by the Russian public. In fact, at a Russian Impressionist exhibit at the Imperial Academy in 1886, visitors stormed out in anger! One art critic at the exhibition made this comment about Nikolai Kuznetsov’s painting, Wild Flowers (1885): “The artist depicts a young woman standing on a hill with a bouquet, from a low horizon, against a background of sky and clouds. The device was so revolutionary that it led to an outburst of ridicule and accusations of immorality.” For this reason these artists were in no hurry to call themselves Impressionists. In fact, they would avoid such terms in describing their work. In his Impressionistic work, Girl Illuminated by the Sun (1888), Valentine Serov recalled, “I must have gone completely off my head then. It should only be done occasionally … otherwise nothing will result.”

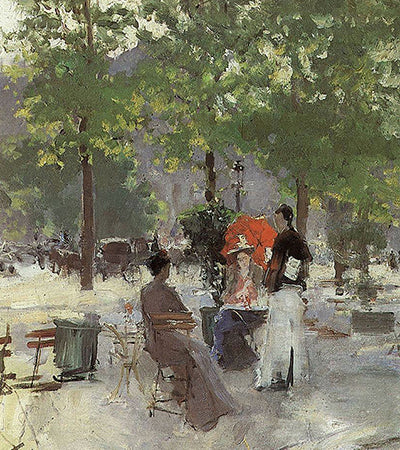

Konstantin Korovin, considered one of the fathers of Russian Impressionism, heard the term “Impressionism” for the first time from his teacher, Vasily Polenov in 1882. Korovin had just returned from St. Petersburg where he had seen the paintings of the Barbizon School in the Kushelev Collection at the museum of the Imperial Academy of Arts. Polenov was the first to teach the concepts of French Impressionism in Russia at the Moscow School of Painting and he was very impressed with how quickly and naturally Korovin took to the style. Besides the use of expressive brushwork, Korovin also started using asymmetrical compositions with fragmented space and form to increase the sensation of dynamism in his paintings. Korovin’s Portrait of Tatyanna Lyubatovich (1880s) depicts this new use of a dynamic composition by sitting the model on a window frame positioned in the upper half of the canvas and having her look directly at the viewer. Within a short period of time Korovin’s style of painting became so popular among young Moscow artists that his studio became the leading place for artists to meet and discuss ideas.

It is no surprise that one of the very first official exhibitions of Russian Impressionism took place in Moscow, organized by the Moscow Society of Lovers of the Arts in December 1888. Valentin Serov won first prize for Girl with Peaches (1887). Korovin won second prize for genre painting with At the Tea Table (1888) and Isaac Levitan won second prize for landscape with At Volga. Evening Falls (1888). The exhibition did not receive favorable reviews neither by the public nor the Moscow press and comments included, “contained no especially outstanding pictures.”

The French Impressionists' aim was to take everyday subjects and recreate them with a painterly quality. Of all the Russian painters, Korovin was the one who most closely worked with the same aim with his work. Typical qualities of French Impressionist paintings include: a strong shadow pattern, colored shadows and fragmented brushwork – elements which are all found in Korovin’s work. These qualities are also found in Igor Grabar’s work, though his technique is closer to the Post-Impressionist style of Divisionism. Other Russian artists who used the fragmented brushwork style of the French Impressionists include: Victor Borisov-Musatov, Nikolai Feshin, Abram Arkhipov, Ivan Grabovsky, Boris Kustodiev and Sergei Vinogradov.

About the Author

Cathy Locke is an award-winning fine art painter, professor, and published writer, specializing in Russian art of the 19th and 20th centuries. She is the editor of Musings-on-art.org.

Cathy Locke’s artwork – www.cathylocke.com