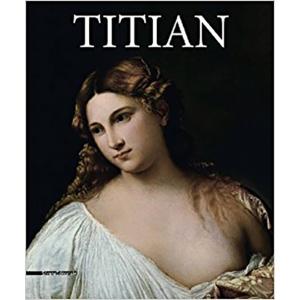

The Magic of Titian

by Cathy Locke

The undisputed master of Venetian Renaissance painting for the last sixty years of his life, Titian (1477–1576) counted Europe’s aristocracy and the pope among his patrons. One of the most versatile of all the Italian painters, Titian was equally adept with portraits as with mythological and religious subjects. He was the first of the Venetian painters to reveal the hand of the painter by the development of his own individual brushstroke. Titian’s work stood out among so many talented artists of his day because of his diverse brushwork, use of color and his application of a wide variety of paint, from thin to thick impasto. These innovations had a profound influence on generations of Western artists to come. In 1487, at around the age of ten, Titian began working in the studio of the elderly Gentile Bellini (1429-1507), then transferred to the studio of the more famous Giovanni Bellini (1430-1516), Gentile’s brother. Some scholars believe Titian joined Giorgione (1478-1510) as an assistant around 1505; however the great biographer Giorgio Vasari (1511-1571) wrote that Titian did not work directly under him, but admired Giorgione’s work and copied his techniques.1 Either way their relationship contained a significant element of rivalry. “One of the earliest known Titian works, Christ Carrying the Cross (1505) in the Scuola Grande di San Rocco, was long regarded as by Giorgione.”2 Toward the end of his career Giorgione began softening the edges of his figures creating a blurred edge. This technical device maximized the sfumato effect of integrating the figure into its surroundings conveying a heightened sense of atmospheric perspective.3 He also started using cooler colors in the shadows, making the warm colors stand out. There are two interesting paintings by these masters in the collection of the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia: one of Giorgione’s last works, Judith (1510), and The Flight into Egypt (1506), an early Titian painting. Initially purchased by Catherine the Great in 1772, Judith was believed to have been painted by Titian. Years later the Hermitage curators discovered that Judith was painted by Giorgione. Since there are only about six surviving paintings in the world today by Giorgione, this became a very valuable discovery. Comparing the two paintings one can see the exact same color palette of cool blues and greens, with the warm red and golden colors in the fabrics. Titian’s composition is more static with the central characters looking like they are walking across a stage in single file. Giorgione on the other hand masterfully moves our eye around the central character from her head flowing down to her foot, which is ever so gracefully placed on top of Holophernes’s head. This poetic movement that Giorgione has so mastered is actually known as a "poesie." The lyrical, charming image of Judith herself and the coolness of the morning landscape create the mood of poetic thoughtfulness, which is not disturbed even by the severed head of the enemy commander.

Portraits

Able to highlight the most positive traits of his patrons Titian was particularly successful with his portrait work. For two years (1534-36) he worked on the portrait of Isabella d’Este (1474-1539), Marchioness of Mantua, a key political and cultural leader of Renaissance Italy. Titian painted her as a twenty-something beauty, with soft skin unblemished by wrinkles, in the bloom of her youth, when in reality, she was in her sixties. This portrait demonstrates the artist’s skill in differentiating the textures of flesh, hair, velvet and fur. We can also see Titian’s magic with textures in his portrait of Jacopo Strada (1567-68), a prominent art dealer. “According to the renowned biographer of the artists’ lives, Giorgio Vasari, ‘there was almost no famous lord, nor prince, nor great woman, who was not painted by Titian.’”4

Painting System

Titian developed a color blocking system that has been taught in art schools since his death. He used a very thick rough weave for his canvases, which were prepared with an oil based white lead paint mixed with chalk. Beginning with the central figure he would block out all the shapes in a generalized color and value. Next he would develop modeling and chiaroscuro shadows. Skin was done with very thin layers of paint with a lot of medium and painted on like a glaze so that the colors underneath showed through. Fabrics were painted a solid color then textures were created with a dry brush technique on top. Backgrounds were painted very thinly, often very dark to increase the drama of the central figure. During his painting process Titian would often set the canvas facing the wall for several weeks and come back to it with a fresh eye. One can see this level of ‘finish’ in the surface quality of his paintings. Today, however, it is difficult to find a Titian painting that hasn’t lost his magical brushwork due to restoration. But, for many years, thousands of aspiring artists would study his techniques. By 1530 Titian had made it to super star status and began increasing the drama in his work through complex compositions and heightened value contrast. This increased drama was a contributing factor to the development of the Baroque style of painting.

The Danaë Series

At the height of his career Titian and his large workshop were mass producing paintings for Europe’s wealthy. One such painting was Danaë, which there were at least five versions painted between 1540 to 1570. In all four of the surviving versions Danaë is a voluptuous woman dominating the composition with her legs slightly apart. Titian used courtesans as models for these types of paintings. There are slight differences between each version, which most likely shows the creative process between Titian and his patrons. The first version, Danaë with Eros (1544), was painted in Rome for Cardinal Alessandro Farnese and is now in the Capodimonte Museum in Naples. In this more modest version the partially clothed Danaë and Eros look upon Jupiter who is disguised as a shower of gold coins. The fourth version, Danaë (1564), is attributed to Titian’s workshop and is located today at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. Here we see a much more heavier treatment of Danaë’s skin-tone and drapery with Jupiter’s face at the top of the canvas.

Late Work

During the course of his long life, Titian's artistic style changed drastically. Although his mature works may not contain the vivid luminous tints of his early pieces, their loose brushwork and subtlety of tone are without precedent in the history of Western painting. Titian’s tonal approach created a rich painterly style, with a distinct shift toward a more emotional dramatic painting. Titian painted many versions of Mary Magdalene over his career, but the version at the Hermitage Museum, The Penitent Mary Magdalene (1560s), is unrivaled for its emotional quality. Renaissance painting has produced few works which can match the emotional force of Titian's depiction of the woman alone in the desert atoning for her sins, her face tear-stained, her gaze soaring upwards to the heavens, her hand pressed to her breast – the perfect image of a troubled soul. St. Sebastian, one of the artist’s last works, also depicts a strong emotional quality. Generations of people were shocked by the freedom and boldness of the painting’s brushwork, so much so that it was not considered worthy of exhibition until 1892 when taste in art changed. Titian kept both of these paintings for himself in his studio at his home. Perhaps Titian didn’t intend to keep these paintings for himself, as he was an insatiable perfectionist, unable to part with some paintings for up to ten years. After Titian’s death his son Pomponio sold his house and all its contents in 1581 to the aristocrat Cristoforo Barbarigo (d.1600). The Penitent Mary Magdalene and St. Sebastian (1570s) then became the property of Barbarigo. In 1850, when Tsar Nicholas I purchased the greater part of Barbarigo’s collection from his surviving relatives, the collection at the Hermitage Museum became second only to Philip II’s collection at the Museo del Prado in Madrid. It was said that Titian was recognized by his contemporaries as The Sun Amidst Small Stars, recalling the famous final line of Dante's Paradiso.

Sources:

1. Giorgio Vasari, Vasari’s Lives of the Artists, Dover Publications, 1967; pages 220-221.

2. Charles Hope, in Jaffé, pp. 11–14.

3. Sylvia Ferino-Pagden and Lynn Federle Orr, Masters of Venice: Renaissance Painters of Passion and Power, Delmonico Books, page 74.

4. Sylvia Ferino-Pagden and Lynn Federle Orr, Masters of Venice: Renaissance Painters of Passion and Power, Delmonico Books, page 73.

5. Mikhail Piotrovsky, My Hermitage, Skira Rizzoli, page 142.

About the Author:

Cathy Locke is an award-winning fine art painter, professor, and published writer, specializing in Russian art of the 19th and 20th centuries. She is the editor of Musings-on-art.org.

Cathy Locke’s artwork – www.cathylocke.com