Wassily Kandinsky: A Pioneer of Abstract Art

Wassily Kandinsky was born Moscow in 1866, the son of Lidia Tikheeva and Vasily Kandinsky, a successful tea merchant. Kandinsky’s parents divorced in 1871 and he ended staying with his father’s side of the family in Odessa. His grandmother provided Kandinsky with vital elements to his early education. She not only taught him to speak German, she taught him the fairytales from his family heritage of Germany, Russia and Mongolia. His mother’s sister, Elisabeth Tikheeva, became his main caretaker. She taught him to play the piano and the cello, as well as to paint and draw. “I remember that drawing and a little bit later painting, lifted me out of the reality,” he wrote. Even as a child, Kandinsky had a unique perception of color and wrote, “Each color lives by its mysterious life.”

In 1886 Kandinsky began studying law in Moscow and went on to complete his degree, graduating with honors. In 1891 he married his cousin, Anna Chimyakina. His new wife thought she was settling down as a lawyer’s wife, but Kandinsky grew restless and disillusioned. According to Kandinsky’s own memoirs, he decided to become an artist in 1895 after seeing Claude Monet’s Haystacks at an Impressionists’ exhibition in Moscow. One year later, at the age of thirty, he made a clean break with his legal career and moved to Munich which, at the time, was one of the main centers of the art world. He first enrolled in the prestigious private school of Anton Azbe, then the Munich Academy of Fine Art where he studied under Franz Stuck. During his time at the Academy, he emerged as an art theorist as well as a painter.

Phalanx Art Group

In 1901 Kandinsky co-founded the Phalanx art group along with three fellow artists and was elected director. This association organized twelve exhibitions between 1901 and 1904, featuring not only their own work but those by Claude Monet, Paul Signac and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Through this association he met Gabriele Münter, a German-American artist who at first became his student, then a supportive colleague and later his companion. Kandinsky and his wife Anna divorced in 1903.

Murnau

After the disbanding of the Phalanx group, Kandinsky and Münter traveled extensively across Europe as well as frequent trips to Moscow to take part in numerous art shows between the years of 1903 and 1908. One of which was the famous Fauve exhibition, Salon d’Automne, in Paris in 1905. In 1908 they settled down in the small town of Murnau south of Munich. It was here that Kandinsky began a series of landscapes that he painted in an increasingly abstract manner using a Fauvist–inspired color palette. During this time he also worked on a series of paintings based on Russian fairy tales, one of which, The Blue Rider, became the emblem for his future art group based on the same name. Alexej von Jawlenksy and Marianne von Werefkin visited the couple often, as a group they would paint in the countryside together. Kandinsky’s painting style of this period in his life was close to the Neo-Impressionists, such as Signac, whom he had exhibited with the Phalanx group.

Innovations in Munich

Around 1907 Kandinsky and Münter started following the theosophical writings of Madame Blavatsky, Rudolf Steiner, Annie Besant and other true believers in the occult. Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925) attempted to find a synthesis between science and mysticism, particularly between color vibration and spiritual energy. It was Steiner’s influence that led Kandinsky to write his essay, Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1910), which forever linked his art with the quest for spirituality. Kandinsky felt he had a major break through in his perception of creating art while writing this book. He saw for the first time that art does not depend on formal training but instead on the interior desire of the artist. Kandinsky felt this was a big step forward because it gave him the freedom to overturn all the rules and limits he had been taught. He began creating work where color held the primary function in the painting. Kandinsky stopped painting landscapes and started to create imaginary scenes where form became less important and more abstracted to allow the color to be the focal point. In 1908 Kandinsky wrote, “what must replace the object?” He replied with color and line.

In his book, Concerning the Spiritual in Art, Kandinsky defines three types of painting: impressions, improvisations and compositions. Impressions depend on an exterior reality and serve as a point of departure for the artist. Improvisations and compositions depict images arising from the artist’s subconscious mind. Compositions are the most developed of the three and represent a formal point of view by the artist.

In 1909 Kandinsky, Münter, Alexej Jawlensky and others co-founded The New Group of Artists in Munich where once again, Kandinsky was elected director. In 1910 and 1912 the group exhibited with the Jack of Diamonds art group in Moscow. During this time Kandinsky published a series of critical letters in the magazines, The World of Art and Apollo. It is believed that Kandinsky was also writing for the Russian Symbolist magazine The Golden Fleece during this time. One article in particular, "Painting and Revolution" by D. Imgardt (a name believed to be Kandinsky's pseudonym) was of vital significance to modern art.

In 1909 Kandinsky began working on four experimental dramas for the theater based on color. His work was first published in The Blue Rider Almanac in 1912. The Yellow Sound was the first and most influential. The others were titled, The Green Sound, Black and White and Violet. Kandinsky’s dramas were a blending of multiple art forms with lighting techniques. The Yellow Sound was a one-act opera that was divided into six "pictures," without dialogue or conventional plot. A child in white and an adult performer in black represented life and death while other figures were costumed in single colors. Kandinsky never saw any of his dramas performed. The first performance of The Yellow Sound was planned for 1914, but it was canceled due to the outbreak of World War I.

Artistically, Kandinsky’s theater productions greatly influenced his paintings. In 1909 he began work on a series he called Improvisations that dealt with the theme of life and death. These were semi-abstract paintings where Kandinsky still held on to some elements of form. He was working with a new concept called Sound Painting, where artists incorporate sound into the physical act of painting. Several of these paintings, The War and St. George (Version II) in particular, hang in the Russian Museum.

In 1910 Kandinsky began a series of paintings he called Compositions. Drawing on elements from Russian Symbolism and German Expressionism Kandinsky let go of all representation and began to work in abstraction. He was strongly influenced by the German theater innovator, Lothar Schreyer, who created a theory of performance based on the expressive process.

Blue Rider

In 1911, Kandinsky founded the Blue Rider group along with a number of Russian emigrants including Alexej von Jawlensky and Marianne von Werefkin and native German artists Franz Marc, August Macke and Gabriele Münter. For Kandinsky the rider was a metaphor for the artist. He wrote in the Blue Rider Almanac, “The horse carries the rider with strength and speed. But it is the rider who guides the horse. Talent will bring an artist to great heights with strength and speed. But it is the artist who directs his own talent.” For the cover of the Almanac Kandinsky created a painting of a horse and rider in mid-leap to represent the artist leaping across the distance that separates him from the art to come. This group embraced mysticism much more than the others Kandinsky had formed, focusing on revealing the associative properties of color, line and composition. The Blue Riders were influenced by numerous sources, such as Goethe and Phillip Runge’s romantic theory of color as well as Jugendstil and Rudolf Steiner’s theosophy. The movement lasted from 1911 to 1914 and is known for its fundamental beliefs in spirituality and expressionism.

Return to Moscow

When World War I broke out in 1914, Kandinsky and Münter left Germany in August and moved back to Murnau. Here Kandinsky started his book, Point and Line. By November the couple parted, with Münter moving back to Munich and Kandinsky going to Moscow. As a Russian national Kandinsky had no choice but to leave the place where he had flourished as an artist and return home. In the autumn of 1916 Kandinsky became acquainted with Nina Andreevskaya, the daughter of the Russian General, and they married a few months later in February of 1917. Nina described their relationship as love at first sight; he was 50 years old and she 17. At the end of 1917 they had a son, Wsevoldn, who died in June of 1920, which was devastating to both parents.

At the onset of the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 history took an unexpected turn and the art of the avant-garde suddenly was in a position of power. Avant-garde art became the new voice of Lenin’s government. Though Kandinsky never became a Communist, he gained immense prestige as a prophet of the new abstract art. He was given official positions and he enthusiastically embraced his role as cultural bureaucrat and teacher. The Revolution held a promise of spiritual renewal that both Kandinsky and Malevich embraced. Kandinsky was part of the committee that dealt with the nationalization of the wealthy’s art collections. He was also very involved with the reorganization of the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow. From 1918 until 1921 Kandinsky worked with the People’s Committee of Education in the capacity of art training and museum reform. He became the chairman of the State Purchasing Commission at the Museum Bureau and participated in the founding of twenty-two provincial museums. During this time period Kandinsky wrote On Materialism in Art, which was not published until 1926.

Over time Kandinsky became a major figure in the ideology of the Russian Avant-Garde. In 1918 Kandinsky taught at the Moscow Svomas (Free Workshops) and then at Vkhutemas. He developed a curriculum based on the analysis of color and form through his book, On the Spiritual in Art. He founded and managed the Moscow Institute of Artistic Culture (INKhUK) where he also taught his theory.

During this time Kandinsky's paintings became increasingly geometrical, influenced by Malevich’s Suprematism. From 1920 to 1922 all of the new theories of the Russian Avant-Garde were passionately discussed and revised in a series of debates at INKhUK. Kandinsky was vehemently opposed to the Constructivist theory of his colleagues who, in return, attacked his works by calling them “mutilated spiritualism.” Because of his mysticism and conflicts in theory, Kandinsky was deposed as chairman. During this period, he rarely painted, choosing instead to draw works on paper.

Bauhaus

By 1921 the Communist Party’s propaganda machine was beginning to shift their preferences in art. Kandinsky was feeling the pressure of Soviet ideology forcing artists to create what was to become Socialist Realism. In 1921, during an “official mission” in Germany, Kandinsky decided to remain there with his wife Nina. Walter Gropius, director of the Bauhaus Movement, offered him a position teaching mural painting, a discipline he knew little about. He used this opportunity to create several monumental decors, including the entrance hall for the 1922 Juryfreie Exhibition and the Music Room at the Strasbourg Modern Art Museum in 1931. With his murals he did a number of technical experimentations including linocuts and painting on the reverse side of glass. Kandinsky’s aim was to find the appropriate form for the content that he wished to express.

While at the Bauhaus, Kandinsky remained aloof to the social mission of the school to separate from the failed ways of the past and to align with new ways of thinking. The Bauhaus moved away from the emotional and ornate, turning toward all things rational and functional. The school was founded on the same concept as Lenin’s Vkhutemas, the ideal of bringing together art and architecture to create a “total” work of art. The very foundation of the Bauhaus was formed on the utopian ideal of geometric form, which they inherited directly from the Russian avant-garde. Geometric form had become the symbol of modernist art and Kandinsky’s work during this time represented the ideal in geometric form. While at Bauhaus he published, Point and Line to Plane, a treatise that aligned with Kandinsky’s metaphysical theories and aesthetic analysis, but was completely void of social philosophy.

Kandinsky kept his position at the Bauhaus until the school’s closure in 1933 when Hitler came into power and declared abstract art "degenerate." At this time Kandinsky's German nationality, which had been obtained in 1927, was revoked. While living in Moscow the artist had been suspected by the left-wing of having sympathies with the White Russians because of the wealth of his family. The Germans suspected him of Bolshevism because he had worked for the Soviets after the 1917 Revolution. The stateless Kandinsky was caught between two political lines of fire and decided to move to Paris.

Biomorphic Abstraction: His Final Chapter

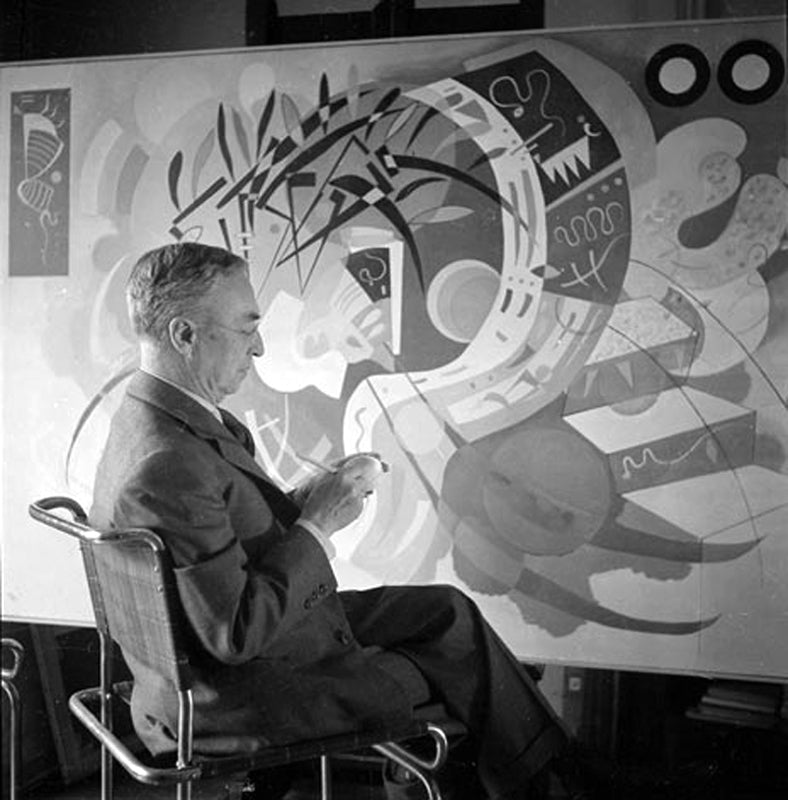

Kandinsky spent the last years of his life living in a small apartment located in the Paris suburb of Neuilly-sur-Seine. In Paris Kandinsky felt isolated from his colleagues; he was no longer at the center of creative discussions and debates. He had little connection with the educational system in Paris and the Parisian art world took little notice of anyone outside their circle. He was opposed to the influences of the Communist Party and unsympathetic to the doctrines of the Surrealist. He did not fit into any of the factions of the Paris art scene at that time. Recognition was essential to his survival, but he had to be extremely discreet about voicing his true opinions. It was a difficult time as paintings rarely sold and he became extremely depressed. At a time in his life when most artists would just build on what they had already developed, Kandinsky instead created an entirely new direction for his art. Instead of using bright primary colors, he worked with a more muted color palette focusing on subtle nuances of color. For subject matter Kandinsky started working with biomorphic elements floating over the surface of his canvas. For inspiration Kandinsky used the minuscule population of embryos, larvae and invertebrates. One can’t help but recognize the symbolism of Kandinsky’s subject choice. At a time when he had become invisible to the art community he choose to focus on a world of life invisible to the eye. One of the statements he made in Point and Line to Plane summed up this final direction: “Not everything is visible and tangible, or – to be more explicit – under the visible and comprehensible lies the invisible and incomprehensible.”

These years in Paris were very prolific for Kandinsky. He completed one hundred and forty-four oil paintings; more than two hundred and fifty watercolors and gouaches; and several hundred drawings. He created a new world of abstract art with his biomorphic paintings which he called a “cosmic world juxtaposed to the world of nature.” He went on to say that his “world of art” is just as real and just as concrete. He labeled his new abstract art as “concrete art.” Up to the very end Kandinsky never doubted his work and felt he was creating a new language of art. In this last body of work he was compared to his contemporaries Miro and Arp, who he had adapted many ideas from. He was granted French citizenship in 1939 but always felt like an outsider.

Notes

Kandinsky lost a number of his paintings on two separate occasions. When he left Munich for Moscow in 1914, he entrusted his work to Gabriele Münter. After his marriage to his second wife, Nina, he never saw this work again. The paintings were not rediscovered until 1956 when Münter bequeathed them to the city of Munich. The second loss occured when many of his paintings were appropriated by Lenin’s nationalization. Due to Stalin’s low opinion of abstract art, these works remained inaccessible until 1963, when some of them were exhibited during the first real retrospective devoted to the artist, organized by the Guggenheim Museum in New York. In 1973 Nina Kandinsky published a book of memoirs, Kandinsky and Me.

The Kandinsky Society

In 1979 Nina Kandinsky created the Kandinsky Society, a not-for-profit associated headquartered at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. This society unites the directors of three museums: The Lenbachhaus Museum in Munich, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York and the Centre Pompidou. The society’s vocation is to watch over the integrity of the work and to publish books on Kandinsky’s work.

Prints Available by this Artist

Sources

Docent lectures at the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg Vassily Kandinsky, Centre Pompidou website Kandinsky in Paris, by Hilton Kramer, The New Criterion Wassily Kandinsky, Wikipedia

About the Author

Cathy Locke is an award-winning fine art painter, professor, lecturer and published writer, who specializes in Russian art of the 19th and 20th centuries. She is the editor of Musings-on-art.org.

Cathy Locke’s artwork – www.cathylocke.com